)

Did you know food and drink such as apples, avocados, brazil nuts, cocoa, coffee, kiwis, strawberries, and tomatoes rely heavily on insect pollination to be produced?

Without pollinators, these products would be in short supply, and some, like cocoa, might not exist at all.

As well as food and drink, pollination is vital for plant reproductive success, medicines, and ultimately human and animal survival.

The value of pollinators in the UK is around £6-700 million per year1 and globally up to $577 billion per year, highlighting just how much they contribute to our economy.2

When we learn that globally around 88% of flowering plant species are pollinated by animals and 75% of the world’s major crop species in some way benefit from animal pollination, we can begin to understand the catastrophic effect it would have if these pollinators declined.2

Currently, we know 9% of Europe’s bee species are threatened with extinction3, but for 56.7% of European bee species we don’t have enough data to predict how much danger they are in. Pollinator decline could therefore be worse than we already know it to be.

Pollinators don’t just include bees – other insects, bird species, primates, rodents, and marsupials are also on the list. For example, UEA research found that when vertebrates such as birds and bats are prevented from feeding from flowers, this can decrease the seeds and fruits produced by the plant by around 63%.4 The animals who feed on these seeds and fruits would then suffer dramatically.

Why are they declining?

Our landscapes have changed over time, largely due to changes in agricultural practices. Agriculture no longer ensures landscapes are flower-rich. We rely heavily on chemicals to fertilise land and to protect crops against pests, including flowering weeds. Very large scale loss of habitats such as meadows and heathlands over the 20th century has led to loss of flowers, which in turn leads to declining populations of insects that feed on flowers. Bees eat only nectar and pollen throughout their lives, so without the flowers they cannot survive.

Along with this loss of basic food and nesting resources, pollinators face a compendium of other threats, including insecticides, diseases and climate change, all acting together to make their lives more difficult.

Although agriculture goes some way to explain the cause of pollinator decline, it also goes some way to solving the problem.

Dr Lynn Dicks, who is currently researching how farmers, policymakers and businesses can respond to pollinator decline within UEA’s School of Biological Sciences said:

"Agriculture plays a huge part. while it is partly responsible for pollinator decline, it can also be part of the solution. practices that support pollinators, such as managing landscapes to provide food and shelter for them, should be promoted and supported."

"We also need to focus publicly funded research on improving yields in farming systems like organic farming, which are known to support pollinators"

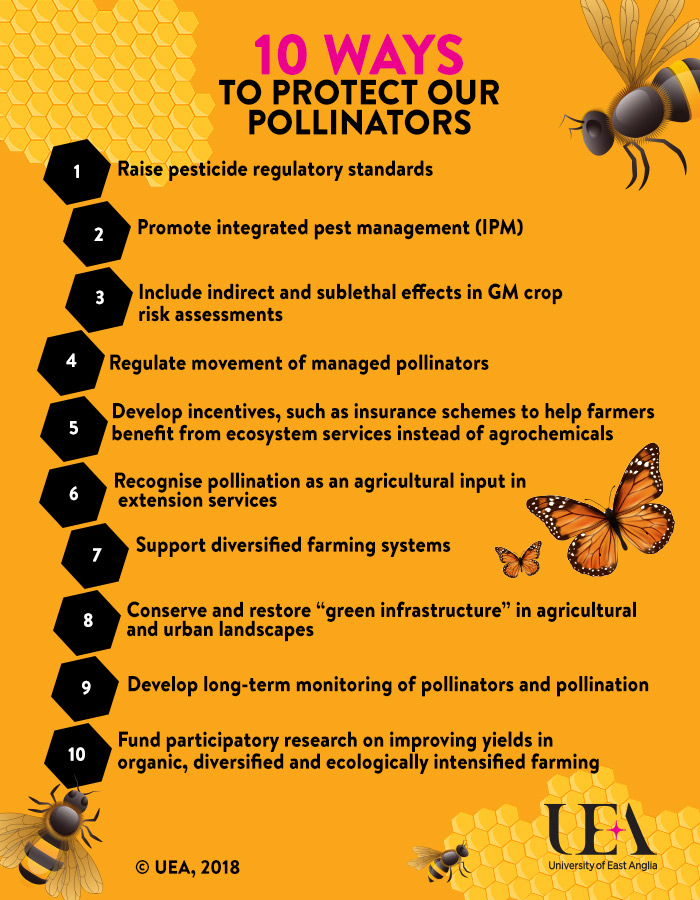

Dr Dicks and colleagues came up with a list of 10 policy suggestions that Governments around the world could use to help reduce pollinator decline.5

How much worse could the situation get if we don’t act?

Pollinator decline also affects companies. Asda, Body Shop, Mars and many more could see their prices rise, or products vanish from shelves, if conservation practices aren’t put in place.

A report funded by Cambridge Conservation Initiative found a lot of companies weren’t knowledgeable about which of their crops relied on pollinators and which ones were potentially at risk.6

UEA’s research team have looked into which crops are vulnerable from pollinator decline, and a product found to be at significant risk is cocoa.

Dr Dicks said:

Pollinator decline is a serious issue for crops where wild pollinators are important to production and can’t easily be replaced, because managed bees can’t do the job

What are we going to do about it?

It is clear that we all need to be aware of the work pollinators do and play a part in the solution.

Research by Professor Andrew Bourke, who works within UEA’s School of Biological Sciences, looked at new ways to gather essential genetic and ecological information on bumblebees, which are key wild pollinators in the UK and other temperate regions, some species of which are in severe decline.

The research was funded by the Insect Pollinators Initiative and was part of a collaboration with several other institutions led by the Centre for Ecology and Hydrology. The research team used field ecology, remote sensing, microsatellite genotyping and landscape modelling to determine how bumblebees use the landscape in relation to the position of flower patches7. The team non-lethally sampled DNA from 2,101 bee workers and 547 queens across 5 species of wild bumblebee. Back in the lab, the team analysed this DNA to work out family relations. They also used remote sensing and field surveys to create a detailed map of the landscape. Knowing which workers were related to other workers, along with where they foraged in the landscape, revealed how far workers fly from their nest to forage. Depending on the species, this averaged 272 m to 551 m. However, if a worker’s colony was in a landscape with fewer flowers, some would fly over 2 km.

These findings confirm the need for, and importance of, agri-environment schemes for pollinators, as these schemes aim to create high densities of forage patches that reduce workers' foraging distances, and highlight the spatial and temporal scale of the floral resources required for the schemes to be successful.

Along with Dr Dicks’ work, these findings have contributed to the design of the Wild Pollinator and Farm Wildlife Package in the Government’s Countryside Stewardship programme, which gives farmers and land managers incentives to manage the farmed landscape in a sustainable manner, including via measures to aid pollinators.8

Work in Andrew Bourke's group with PhD student Ryan Brock and former MSc and PhD student Dr Liam Crowther has been investigating the genetics, behaviour and ecology of the Tree Bumblebee (Bombus hypnorum), which, highly unusually for a bee, has rapidly increased its range in Britain since arriving as a natural colonist in southern England in 2019. In this work, the team aims to pinpoint how some bees can buck the trend of bee decline.

In Dr Dicks’ group, PhD student Sarah Barnsley is working with the agronomy company Hutchinson’s Limited, to help UK farmers assess what resources their landscape provides for pollinators and use this information to manage the land better for pollinators, and for wildlife more generally.

Almost on the other side of the world, Dr Liam Crowther is now working with an international consortium of researchers, led by UEA, on enhancing the sustainability of fruit production in the highly biodiverse semi-arid caatinga in Brazil. This new project will be testing the effects of changes to farm management on wild bee populations, pollination services and other biodiversity.

Despite these efforts, more needs to be done.

Below is a video of wild bees feeding in a well-established pollen and nectar mix which was shot by a Norfolk farmer last summer.

How many bumblebees can you count in the film?

(video credit: Nick Anema)

What can you do?

It’s not just companies and farmers who play a part in reducing pollinator decline - we all can. For example, gardens are really important for pollinators, plants and human health. You can select flowers to grow that provide resources to pollinators. Bees don’t benefit from double/ triple petaled flower varieties as, in these, the anthers are replaced with petals, and no pollen or nectar is produced. So opting for the varieties that have good levels of nectar and pollen is wise – garden centres now often tell you on the labels how much they contain.

Avoid insecticides too and garden organically!

And if you don’t have a garden, taking care over what you consume is another route to helping pollinators. Eating organically can help wildlife. And even simply raising awareness of the nature around us by telling others why pollinators matter to our world is an effective way of spreading the knowledge.

Other researchers at UEA/ Norwich Research Park in this area:

Sarah Barnsley, Research Student, School of Biological Sciences

Lorna Blackmore, Research Student, School of Biological Sciences

Ryan Brock, Research Student, School of Biological Sciences

Liam Crowther, Senior Research Associate, School of Biological Sciences, currently in the School of Environmental Sciences

Dr Richard Davies, Lecturer in Biodiversity, School of Biological Sciences

Get involved in helping pollinators:

www.gov.uk/government/news/bees-needs-food-and-a-home

www.bumblebeeconservation.org/bees-needs/

Get involved with monitoring pollinators:

www.ceh.ac.uk/our-science/projects/pollinator-monitoring

More on this research:

Press release: Supply chains at risk as wild pollinators decline

Press release: Study highlights importance of Vertebrate Pollinators

Dr Lynn Dicks' full London Lecture

Managing farmed landscapes for pollinating insects

What is causing the decline in pollinating insects?

Related information:

Sources:

1 Carvell et al (2016). Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra), Scottish Government and Welsh Government: Project WC1101.

2 IPBES (2016) Summary for Policymakers of the Assessment Report on Pollinators, Pollination and Food Production. Intergovernmental Science Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services, Bonn.

3 www.ec.europa.eu/environment/nature/conservation/species/redlist/downloads/European_bees.pdf

4 Ratto, F., Simmons, B. I., Spake, R., Zamora-Gutierrez, V., MacDonald, M. A., Merriman, J. C., Tremlett, C. J., Poppy, G. M., Peh, K. S., Dicks, L. V. (2018) Global importance of vertebrate pollinators for plant reproductive success: a meta-analysis, in Frontiers in Ecology & the Environment 16 (2) pp. 82–90.

5 Dicks, L. V., Viana, B., Bommarco, R., Brosi, B., del Coro Arizmendi, M., Cunningham, S. A., Galetto, L., Hill, R., Lopes, A. V., Pires, C., Taki, H., Potts, S. G. (2016) Ten policies for pollinators, in Science 354 (6315) pp. 975-976.

6 Cambridge Institute for Sustainability Leadership, Fauna & Flora International, University of East Anglia, & UNEP-WCMC (2017) The pollination deficit: Towards supply chain resilience in the face of pollinator decline. UNEP-WCMC, Cambridge, UK, 42 pp.

7 Carvell C, Bourke AFG, Dreier S, Freeman SN, Hulmes S, Jordan WC, Redhead JW, Sumner S, Wang J, Heard MS (2017) Bumblebee family lineage survival is enhanced in high quality landscapes. Nature 543: 547-549. www.nature.com/articles/nature21709

8 Dicks, L. V., Baude, M. , Roberts, S. P., Phillips, J. , Green, M. and Carvell, C. (2015). How much flower‐rich habitat is enough for wild pollinators? Answering a key policy question with incomplete knowledge. Ecol Entomol, 40: 22-35. doi:10.1111/een.12226

9 Crowther LP, Hein P-L, Bourke AFG (2014) Habitat and forage associations of a naturally colonising insect pollinator, the Tree Bumblebee Bombus hypnorum. PLoS One 9: e107568 http://journals.plos.org/plosone/articleid=10.1371/journal.pone.0107568

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)