) 27 June 2023

27 June 2023

How do we determine what the biodiversity of an area could be in 25 years' time?

That’s the complex question that Professor Andrew Lovett and his team in the School of Environmental Sciences are getting to grips with as they work on the Norfolk and Suffolk local nature recovery strategies.

It's well understood now that climate change is placing enormous pressure on the natural world, both locally and globally, and that human influences have caused decline in the extent and condition of many natural assets in the UK. And so there is an urgent need to understand the current situation and how interventions could intersect and influence each other.

The local nature recovery strategies are required by law under the Environment Act 2021, and are formed of three key pillars:

- agreeing priorities for nature recovery

- mapping the most valuable existing areas for nature

- mapping specific proposals for creating or improving habitat for nature and wider environmental goals.

Different data sets

So where to begin? Initially, with a huge amount of conflicting data about what actually makes up those areas, Prof Lovett explains.

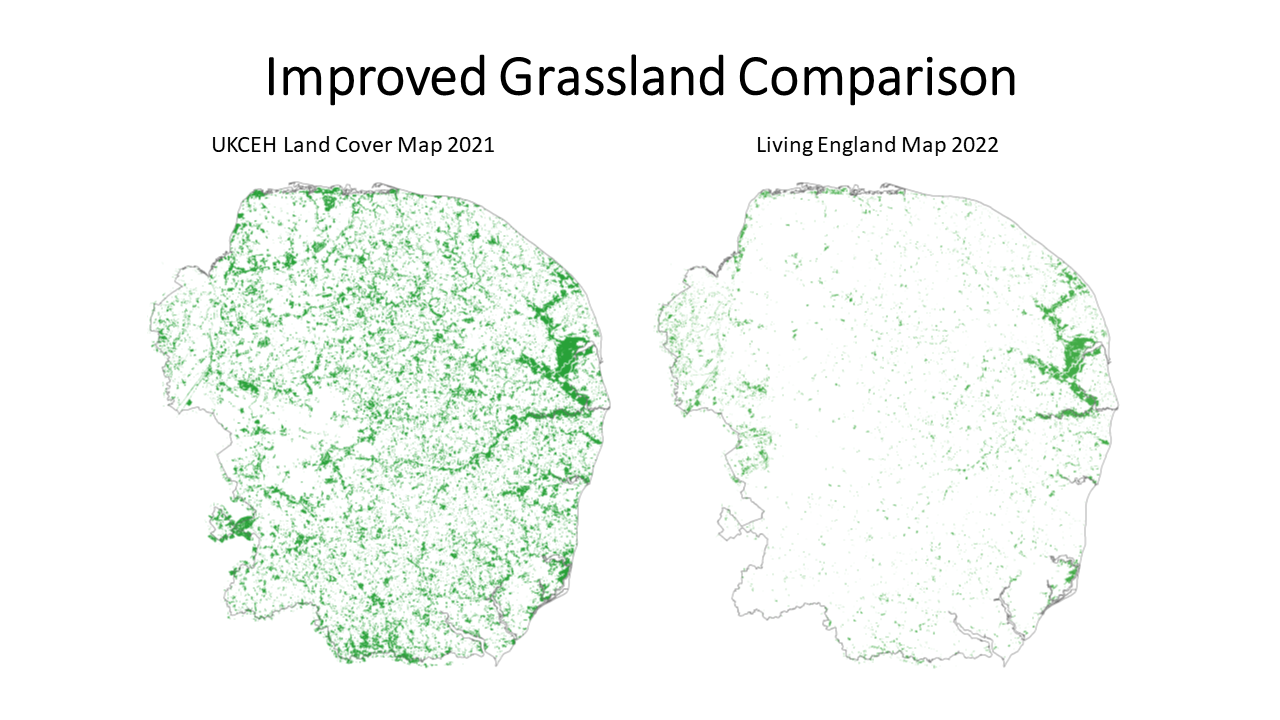

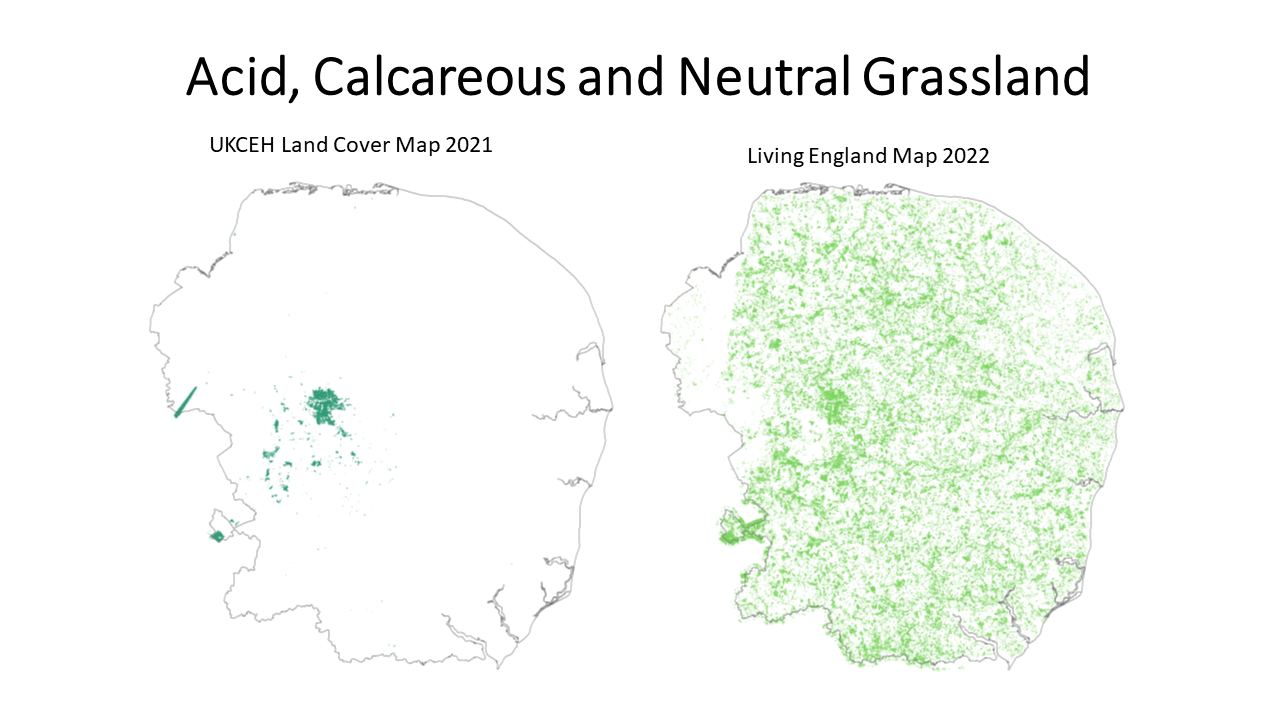

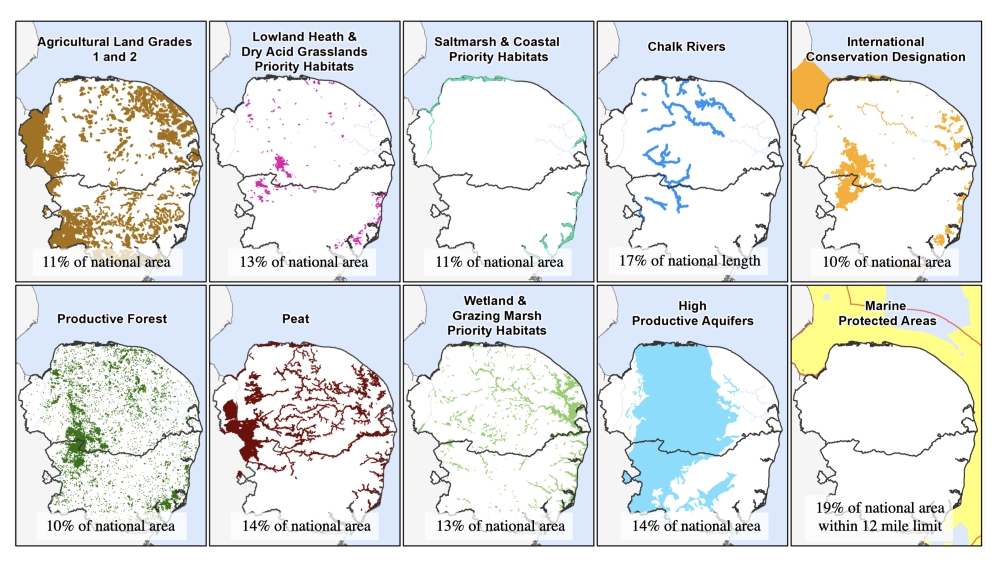

"Lots of different data sets exist to define those sorts of things," he says. "There are land cover maps, which cover the entire area and say: 'We think the land here is arable land, grassland and so on'. Then there are data sets that define specific types of habitat (woodland or saltmarsh, for example).

"Some of them are produced by research institutes and some are produced by agencies like Natural England. Some exist on a national scale, some at the scale of regions, or counties. Organisations like the Forestry Commission have their own data, and so do big NGOs like the RSPB, the National Trust and so on, and so do some big landowners, because they've commissioned their own surveys."

Unsurprisingly, then, the job of assimilating all of these to create "the best possible underlying baseline" is a challenge, Prof Lovett continues, particularly when the accuracy of some of the data is wildly variable. Much of it comes from satellite imagery, based on reflectance in different parts of the electromagnetic spectrum.

"You can classify areas of land based on their spectral reflectance, how much electromagnetic radiation they reflect in different parts of the electromagnetic spectrum," he explains.

"Different types of land cover have different spectral signatures, and on satellite sensors you can measure the amount of reflectance at different points along the electromagnetic spectrum.

"Different things will have different peaks and troughs, and events. So concrete is very different from water, for example, and very different from trees, and from cropland. And they also differ at different times of year.

"But it's easier to do for some types of habitat than others. Distinguishing water from other things is normally not terribly hard. Distinguishing coniferous trees from broadleaf trees isn't too hard, because if you have a summer image and a winter image, it's quite obvious. But distinguishing certain types of heathland and grassland is more of a challenge."

That means that different datasets have vastly differing levels of accuracy, from as high as 90 per cent to as low as 20 in some cases. Which is why Prof Lovett and his team are hoping to bring in data from other sources, such as the County Biodiversity Information Services, where “people actually go around and see what's there on the ground."

Finding the baseline

At the moment, the situation is "a bit of an argument", he continues, with the government encouraging councils to rely solely on certain satellite maps, while Lovett and his team are "not comfortable or keen" with that option. The deadline to have a "baseline that we’re happy with" is November, he says, and the reliability of that baseline has implications for the even bigger questions that come next.

"The next set of challenges is actually developing ideas for what priorities for nature recovery should be," Prof Lovett continues. "At some point, you have to start engaging with different landowners and you really want to be very sure when you go and speak to those people that you've got the characteristics of their land mapped accurately, otherwise it's not going to be an easy process."

There will be "an awful lot of other organisations" involved in the nature recovery partnership and trying to identify what the priorities should be, he continues, and he predicts "some very interesting debates about them."

It’s likely that the priorities will have a focus on improving connectivity between areas that are currently separate, he continues, because "if you've got a changing climate and conditions, species need to be able to move across landscapes."

"Connectivity is important," he says. "Trying to reduce fragmentation of habitats is important. But trying to do it in ways that achieve multiple benefits is also really important. So, in Norfolk and Suffolk, we need to think about how nature recovery can be achieved in a way that also maintains or even ideally enhances food production, and tourism and renewable energy are also important for rural employment. It's not sensible to try and think about these things in one way."

There’s also the question of whether habitat enhancement and restoration should take place near existing areas or be introduced to those where there’s a lack of biodiversity.

"You can argue it either way," Prof Lovett says. "If you want to achieve a benefit in the short term, you probably try and put things close to connect to what you've already got. If you're trying to achieve environmental enhancement over a longer time scale, you probably think about trying to do something to address the areas which are much less well provided for at the moment. But it's going to take longer, and it's going to take more money to do it.

"I think it will be a matter of trying to work out what is the closest to a no-regrets solution. This is going to be an exercise in trying to identify priorities and it isn't going to be easy."