)

In the late nineteenth century, as the federal government entered the final stages of US nation building with its accompanying conquest and dispossession of Native nations, a glaring question remained unanswered: what should be done with the surviving indigenous peoples who had withstood this onslaught.

Professor Jacqueline Fear-Segal’s research explores how, having forcibly subjugated the warrior societies of the Plains, the government proposed an audacious new solution to the “Indian problem”: deliberate obliteration of all indigenous cultures and assimilation of Native youth into mainstream America through re-education in schools.

Fear-Segal looks in particular at the story of two Ndé (Lipan Apache) children who were subjected to this policy of cultural genocide. Captured and transported two thousand miles to the Carlisle Indian Industrial School as prisoners of war, they never returned home. The children’s family did not know their whereabouts until 125 years later when Fear-Segal made contact with them.

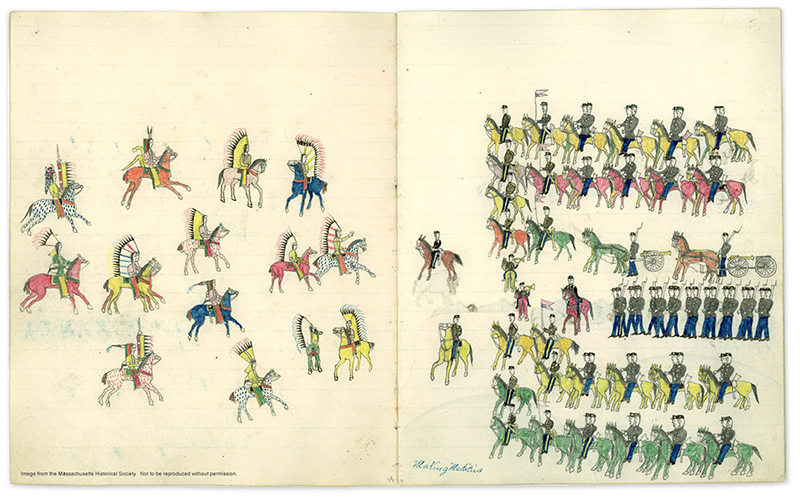

Image: Book of sketches made at Fort Marion, St. Augustine, Fla., 1877 © Collection of the Massachusetts Historical Society

Image: Book of sketches made at Fort Marion, St. Augustine, Fla., 1877 © Collection of the Massachusetts Historical Society

Native nations had their own separate and distinct cultures and had no wish to join the American republican experiment. They powerfully defended their lands and their traditions. But as the United States rapidly became demographically and technologically more powerful, the government cleared the way for white settlement of indigenous lands by organising “Indian” removals and the restriction of all nations to demarcated areas known as reservations.

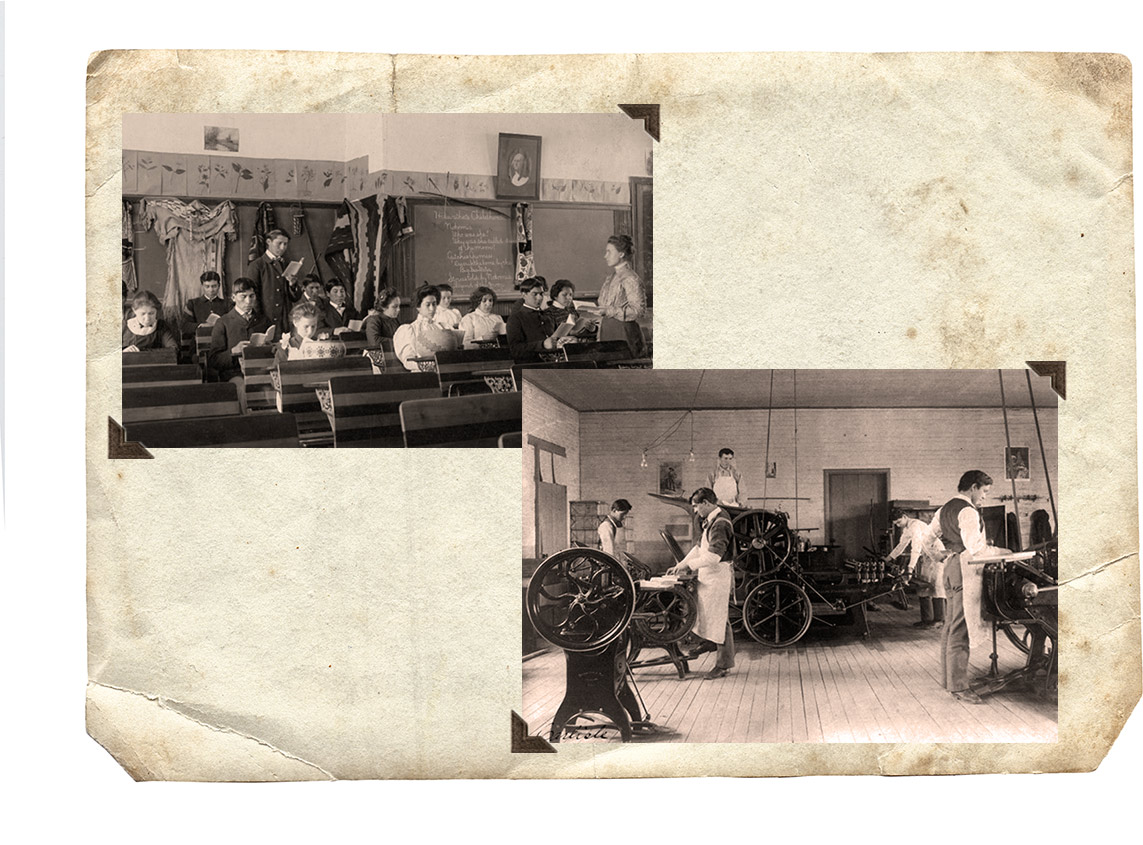

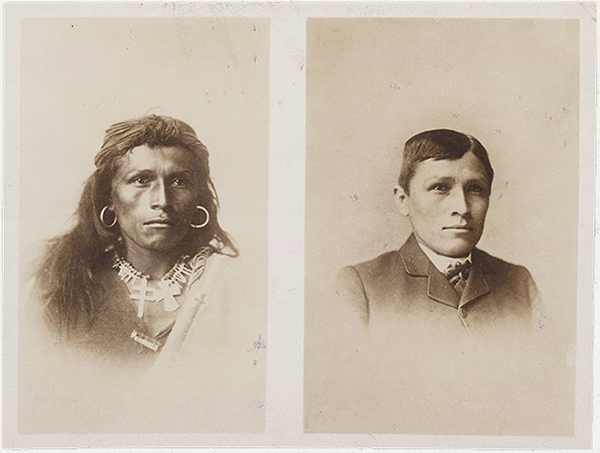

Schools were established on reservations and in the midst of white communities to achieve this goal of cultural genocide. Thousands of Native children from across the USA, Alaska, and even Puerto Rico, were enrolled and instructed to forget their own “inferior” traditions and communities and learn the language, religion, values, and cultural behaviour of Whites.

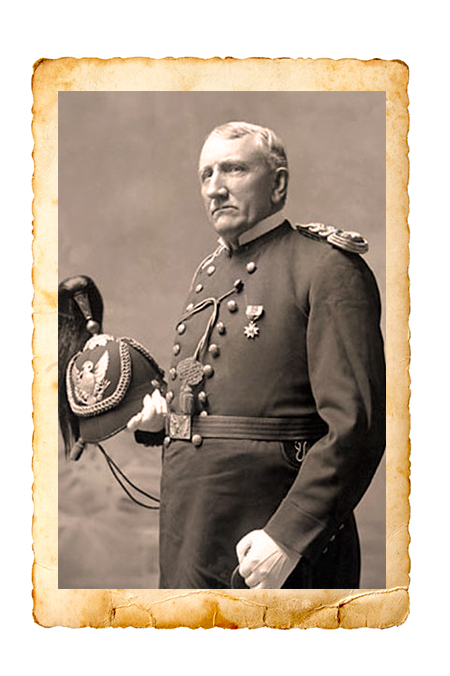

The first government-run Indian boarding school was Carlisle, a living experiment deliberately established far from Indian Country. The Carlisle Indian Industrial School, in Pennsylvania, sought to recruit children from all Native nations and sever their links to homeland, kin, culture, and community. Its founder and first superintendent, Lieut. Richard Henry Pratt, insisted that if separated from their traditional societies and given basic academic and practical schooling, all Native youth, irrespective of background, could be transformed from “savages” to “civilised” English-speaking Americans in a single generation. Pratt moved from fighting Indians to schooling them without shedding his army uniform and ran Carlisle on strict military lines. Carlisle Indian Industrial School provided the model for the Indian school system that would be set up and funded by the government on and off reservations across the USA.

Image: Lieut. Pratt (c) Cumberland County Historical Society, Carlisle Pa

Image: Lieut. Pratt (c) Cumberland County Historical Society, Carlisle Pa

Classroom scenes by F. B. Johnston, National Library of Congress

Classroom scenes by F. B. Johnston, National Library of Congress

Image: 'Tom Torlino before and after' © Cumberland County Historical Society, Carlisle Pa

Image: 'Tom Torlino before and after' © Cumberland County Historical Society, Carlisle Pa

At Carlisle, students spent half their day in the classroom and half learning a trade -- for boys farming, tinsmithing, blacksmithing and similar trades, for girls sewing, laundry and other domestic skills. It was only a very basic education. Out of over 10,500 students who were enrolled at Carlisle (1879-1918) only 758 ever graduated, and very few assimilated into mainstream American society. Instead, the majority went home to their reservations, often after years away. While some were able to make use of their Carlisle schooling, many found it hard to find a place for themselves within their own communities and lived with confusion, stress, and trauma, which were passed down the generations.

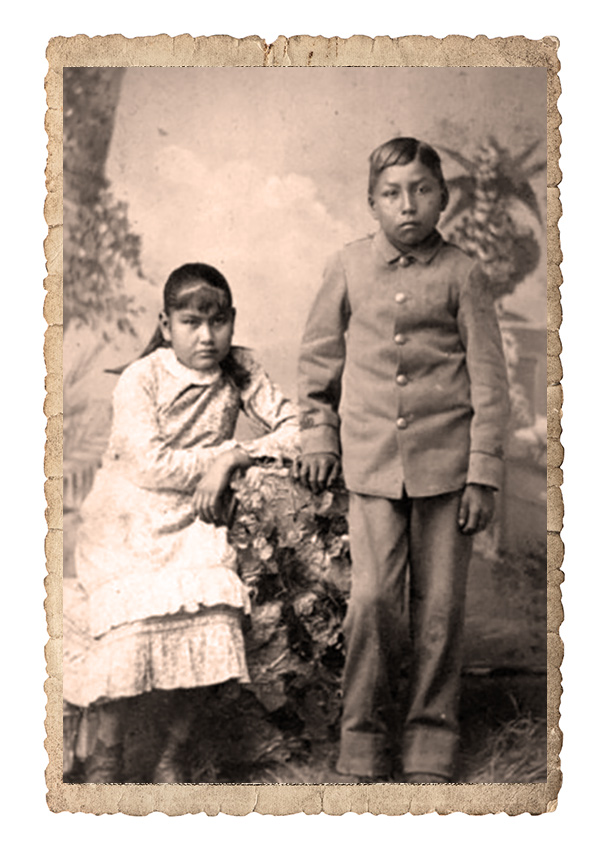

Jack & Kesetta

Image:'Kesetta and Jack' © Cumberland County Historical Society, Carlisle Pa

Jack and Kesetta were enrolled at Carlisle Indian Industrial School shortly after it opened. Born into the Ndé nation (Lipan Apache), they were sent to Carlisle by the US Army as prisoners of war.

The two children had been captured by the Army at El Remolino, Mexico. Colonel Ranald Mackenzie and his 4th US Cavalry made a brutal surprise attack across the Texas-Mexican border. They killed scores of women and children, including Jack and Kesetta’s mother. That day was known for ever after by the Ndé (Lipan Apache) as the “Day of Screams”.

After their capture by the 4th US Cavalry in 1873, Jack and Kesetta never saw their people again.

For some years, Jack and Kesetta lived with an Army family and moved from fort to fort. When the Carlisle Indian School opened, Col. Mackenzie transported them to Pennsylvania, to become part of the government’s assimilation experiment.

The children never again saw their people, who from the time of their disappearance called them the “lost ones”. And this is their story.

It is a story fractured into two parts. The first part unfolds along the Rio Grande River, where the children lived with their people, the Cúelcahén Ndé (people of the long grass). After their capture and disappearance, the Ndé mourned them and kept their memory alive by telling and retelling their story, incorporating it into their oral history. At family gatherings down four generations, a food plate was passed round and chairs always left empty for the “lost ones”.

The second part of the story takes place at the Carlisle Indian School and in Pennsylvania. Fragments of this story, preserved in the written and visual archive, were pieced together by Jacqueline Fear-Segal using Indian School records, newspapers, and photographs.

When Fear-Segal made contact with Daniel Castro Romero Jr., General Council Chairman of the Lipan Apache Band of Texas, these two broken parts of the “lost ones’" story were joined for the first time.

Jack's Story

In 1884, after four and a half years at the school, Jack (now about 16) was sent to St. Augustine, Florida, to live with the seventy-year-old white woman who had adopted him: Sarah Mather. Jack’s journey to Florida by land and sea was long. He passed through New York, Philadelphia, and Savannah, Georgia.

Jack held down several jobs during his time in St Augustine. First employed in a hotel — receiving a wage of $1.25 a day — he was later apprenticed to a local carpenter.

Image: Group of Chiricahua Apache prisoners, including Goyathlay (Geronimo, ca. 1825-1909) (front row, 3rd from right). Image courtesy of the National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution (catalog number P07009). Photo by A. J. McDonald, 1886.

In 1886, the last open Native military resistance in the USA was crushed when the Cavalry captured the famous Chiricahua Apache warrior, Geronimo. This was significant to Jack, because hundreds of Chiricahua Apache prisoners of war captured by the Army in the Southwest were transported and imprisoned in St Augustine – so the Chiricahua Apache language was regularly heard throughout the town. Living in the centre of St. Augustine, Jack would almost certainly have encountered these prisoners and, for the first time since his capture, heard a language close to his mother tongue. He may even have understood some of it.

When Jack fell seriously ill with tuberculosis, after two years in Florida, he was sent back to Carlisle. Arriving into a freezing Pennsylvania January, he joined a group of sickly children in the school hospital. Just two weeks later he passed away and was buried in the school cemetery. When the cemetery was moved and reshaped in 1927, Jack’s new military-style gravestone was incorrectly marked with the name ‘Jack Martha’. It still bears that name today.

Kesetta's Story

Kesetta was about thirteen when she and her brother were enrolled at the Carlisle Indian School. Had she still been living with her own people, at this age she would have participated in a puberty ceremony to celebrate her womanhood in a sacred way and learn Ndé women’s wisdom, passed down by elders. Instead, Kesetta was dressed in the regulation Carlisle uniform and taught to sew and launder, and to drill and march. She and her people were thus robbed of their cultural heritage; a deliberate consequence of Carlisle and the government’s mission of cultural genocide.

Kesetta was named on the Carlisle Indian School enrolment list for over twenty-three years: the school’s longest registered student. But for most of those years she was “out”, working for white families in the region.

Carlisle students were not allowed home for the summer. It was feared that contact with their own traditions would risk them “going back to the blanket” (as it was termed). Instead, they were sent out to work for local families and these “outings” would often extend for several years.

After a short summer outing Kesetta, now about sixteen, began work for the Paxton family. She stayed with this large family for over twelve years, accompanying them when they moved from Pennsylvania to Virginia. But when the Paxton children left home, she chose to return to Carlisle.

With no known family or community of her own, her life became dislocated and itinerant as she moved between different outing households working as a domestic. Three years spent in Willow Grove, just north of Philadelphia, were followed by a year in Columbus, New Jersey, with the Bishop family, who took her to Trenton, New Jersey for a further year. Then a year with the Powells in Milford, Delaware, before her final fateful “outing” to Baltimore, Maryland, when she was thirty five. She returned from Baltimore to Carlisle after a year – except this time, the circumstances were different: she was three months pregnant. Without realising, the outing officer sent her back to the Powells in Delaware. When her predicament became obvious, she was discharged from the school and sent to the Rosine Home in Philadelphia, where, on May 22nd, 1903, she gave birth to a baby boy. With the help of the Rosine Home – an institute run by Quakers for those described as “‘fallen women” – Kesetta found work in Lahaska, a town just north of Philadelphia, and moved there with her infant son, Richard.

Kesetta died of tuberculosis on Christmas Eve, 1906, and was buried in the Quaker cemetery in Lahaska, a town where she was known only as an Indian woman with an illegitimate child. It was a sad end to a tragic life. Although in the historical record Kesetta is silent, leaving no single written word, she left behind her three-and-a-half-year-old son, Richard. When her life ended, her story continued.

The Lost Ones" Long Journey Home Trailer.

Richard, Kesetta's Son

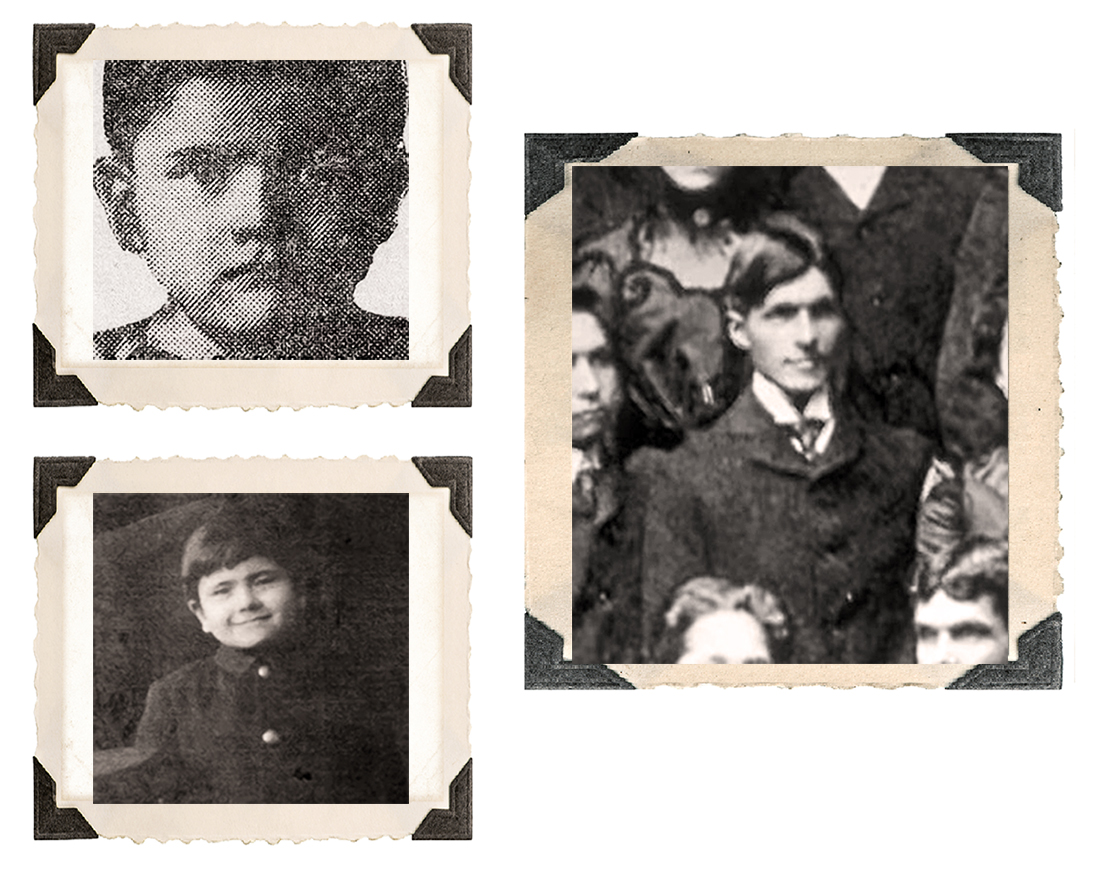

Images of Richard Kesetta © Cumberland County Historical Society, Carlisle Pa

On August 13th, 1907, Kesetta's son Richard was enrolled at Carlisle - the same school that had played such a momentous role in the life of not only his mother, but his uncle too (Jack Mather).

Due to his age (he was much younger than the other Carlisle students), Richard became something of a mascot at Carlisle and, according to the school paper, was "very popular among the large girls".

Richard Kesetta’s Lipan Apache connection, which had shaped and defined his whole life, had been totally erased.

This role of mascot started a trend that would plague Richard throughout his entire life. In 1912, aged nine, he sat on the shoulders of Olympic gold medallist and Carlisle student, Jim Thorpe. As an adult, he was known locally in Carlisle as “the Indian”. And in 1961 he even played the part of a totemic Indian, in full dress-up plains regalia, for a Civil War Centenary celebration. 'Dick' Kesetta, like so many other Native Americans, never escaped the racial stigma of being designated “Indian” and the accompanying incongruous demand to “play Indian”. Yet he never knew who his mother was or his own connection to the Lipan Apache people. Just like hers, his history had been expunged. He, too, was a lost one.

Finding The Lost Ones

Through hours of research and years spent in Washington, DC and Carlisle archives, Professor Jacqueline Fear-Segal sought to piece together the lives of these and other Carlisle students. But the archive can yield only a patchy and brittle record, and so the help and contributions of many other people were crucial to finding, tracing, and telling the story of the “lost ones”.

The most vital and momentous contribution, which enabled the two split parts of the “lost ones’” story to be reconnected, was made by their great great nephew.

Excerpt from Professor Fear Segal’s latest book, ‘Carlisle Indian Industrial School’:

In an attempt to uncover more... I decided to search the internet. A short, website history of the Lipan Apaches included the following paragraph: "In 1861 Ramon Castro and some followers were forced to settle at Fort Belknap, Texas, as a condition of their allegiance to the US government. It was also an attempt to exterminate the Lipan Apache. The US government moved the Lipan Apache people as prisoners of war and in 1867 they transferred the Lipan to Fort Griffin near Albany, Texas. By 1885, less than 20 Lipan Apache Band members were still alive.” This seemed to offer a possible link to Kesetta’s people, so I emailed the author to tell him about the two Lipan children who had been captured by Colonel Mackenzie and sent to the Carlisle Indian School and to ask if he knew anything about them or their band.

The next day, Professor Fear-Segal received the following response from Daniel Castro Romero Jr.:

"It's my understanding that the children were never to be seen or heard from. I would be very interested in knowing the name and location of where they are buried, so that I, and our people, can visit them to give them a Lipan Apache blessing. Ramon Castro was my great-great-great uncle and it is said that the children taken were his children. They were taken from him to test his allegiance to the US government. One of the main reasons why they continued to fight so hard was his sadness over the incident."

Question, how did you find out about this? It's understanding that only family members know about this story.

Daniel Castro Romero Jr

Through Castro Romero Jr., Fear-Segal discovered that Jack and Kesetta were still remembered by their people, and that their story had been told and retold down four generations. She learnt that on the second Saturday in August every year, the Castro family hold a ceremony and feast, with a plate passed round and chairs left empty for the “lost ones”, in remembrance, respect, and the hope for news of their whereabouts.

The two severed parts of the “lost ones’” story were now being reconnected as the separate accounts carried in Ndé oral history and the archival record were brought together.

Fear-Segal next sent pictures of Jack and Kesetta from the Carlisle photograph archive to Casto Romero Jr. in Texas. After doing this, she received the following response:

“On the day I received the photographs, I was standing in line waiting to buy postage stamps when I opened your envelope. For a moment, I could see into my daughter’s eyes, as my eyes watered at the picture of Kesetta. She looks exactly like my daughter. She has the same eyes, facial features, you name it she has it. I was very moved, I could only think of what her parents went through. My ancestors must have been at a loss not knowing where their daughter had gone, never to see her again. She will never again be forgotten, as she has made the journey back home.”

Fear-Segal shared the location of Jack, Kesetta, and Richard’s graves with Castro Romero Jr.. and three Ndé elders travelled across country from Texas to Pennsylvania. They performed Ndé spirit releasing ceremonies to enable the “lost ones” to return home, and to start the healing process the Ndé so desperately needed for their well-being.

That August, when the Castro family came together for their regular gathering, they did not pass round the sacred plate for everyone to put food on for the missing children, or leave out empty chairs. As Castro Romero explained to everyone, there was no longer any need -the children had come home.

“Being able to discover what happened to them and to be able to tell their story, means our sense of space and our sense of spirituality have now been rebalanced.”

“Now the “lost ones” are found, the Ndé can again be strong as people. Fear-Segal ... found our little ones.”

Whatever lies ahead for them in the future, the work of Professor Fear-Segal will always be remembered by the Ndé people, and her name will be forever spoken in their oral history.

The “lost ones” experienced the U.S. government’s campaign of cultural genocide at its most total and brutal. They were taken from their people and homelands when very young, never to return, and they remained classified as prisoners of war for the rest of their lives. The “lost ones” were just two of the many thousands of Native American children transported to government boarding schools deliberately organised to “kill the Indian to save the man”.

Castro Romero believes that every single one of their individual stories needs to be traced and told, so that Native peoples can know and understand this painful aspect of their histories that touched every Native nation.

Retracing & Telling Their Stories...

At Carlisle, the Farmhouse where students lived and trained still stands and was recently rescued from demolition. The Carlisle Indian School Farmhouse Coalition is now working to renovate and restore the Farmhouse as a Heritage Center, to house, protect and make known the history of this school whose mission was the obliteration of all indigenous languages, cultures, and traditions.

Equally important is the need for all Americans to learn about and understand the lasting social, cultural, and psychological legacies left by the Indian boarding school system. To this day, many facets of Native cultures remain lost or disrupted, and Native communities still carry the enduring scars left by schools that were systematically organised to achieve cultural genocide.

Image:'Carlisle Indian School Farmhouse' © Cumberland County Historical Society, Carlisle Pa. Modern Farmhouse image © Carolyn Tolman

Sources

The Lost Ones - The Long Journey Home

Cumberland County Historical Society, Carlisle, Pa

Carlisle Indian School Digital Resource Center

Carlisle Indian Industrial School, (2016) Edited by Jacqueline Fear-Segal and Susan D. Rose

White Man's Club, (2007)Jacqueline Fear-Segal

Top: Lipan Apache Band of Texas symbol

Bottom: Carlisle Indian School logo