Meet the writer who used his UEA degree to fuel a career in human rights

By: UEA Alumni team

Brian Dooley is a Human Rights writer and activist, and Honorary Professor of Practice at Queen’s University, Belfast. He has appeared in international media including BBC News, New York Times and the Washington Post, and has previously held communications posts in Amnesty International and as an advisor in the UN.

Brian graduated from UEA in 1986 with a BA in American History and Politics and returned to UEA to complete a PhD in 2017. He kindly sat down with us to discuss his year before UEA in apartheid South Africa, an obsession with the Kennedys, and why he’s still hungry after a long career.

How did you come to study American studies at UEA?

I went to UEA 1982 after failing my A levels. The School of English and American Studies had started a pilot course called American History and Politics with just seven students. We were promised that as part of this course we would spend the third year in America on an exchange.

What was the attraction? Well, speaking for myself, university was free then, and if you did a four-year course, you got four free years.

Brian Dooley (Right) with friends at UEA

And how did you find studying American Studies at UEA?

My parents hadn’t gone to university, and to begin with, I struggled and didn't take it very seriously. We had to do what were called prelims for the first two terms, which was essentially learning how to study. I borderline passed those. I was just there having a good time for a while. Then, by the second year, it kicked in, and I started to get interested.

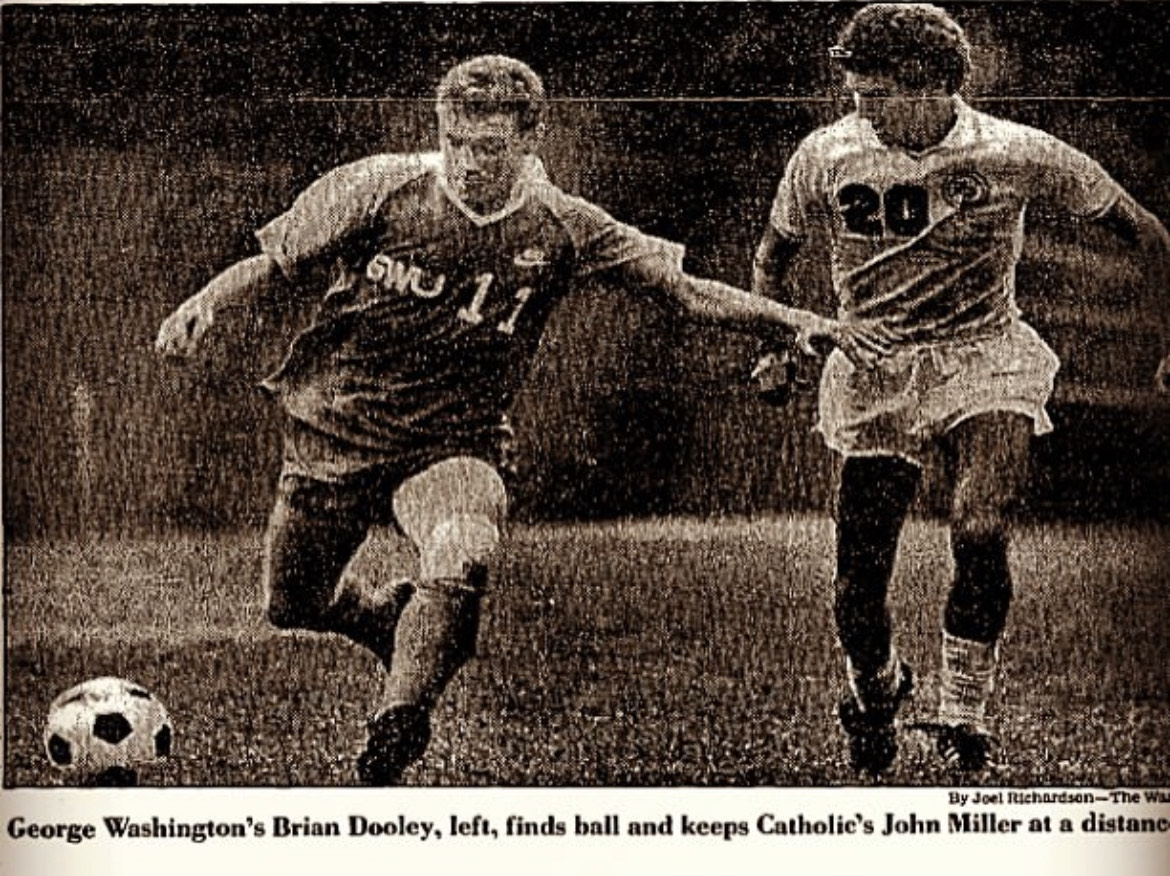

In the third year, I went to Washington along with all those who ended up finishing the course. We studied at the George Washington University, and I don’t think there were many expectations from us in terms of getting good grades there - the course was still in its infancy. I played football for the university team, which was fairly intense compared to playing for UEA. In America, it’s almost a full-time occupation during the season. In the second half of the year, I interned in Washington in Congress for Senator Ted Kennedy. Others on the course also interned for different senators. We were allowed to work, and we took jobs and made some real money. I worked on a building site in California when - in '84-'85 - the pound and the dollar were about at parity, and the wages were good. I got rich.

Did you have a career in mind when you started studying American History and Politics?

The truth is that I can't exactly remember what I was thinking at 17 or 18. I failed my A levels at secondary school and then, through a bizarre set of circumstances, I ended up in in South Africa during apartheid, living with my uncle, who was the parish priest of a large Black Township called Madadeni. That experience was, I think, why UEA was prepared to take me on. I think, when I started at UEA, I probably wanted to be centre forward for Manchester United as much as I wanted to be a journalist.

I had a bit of a historical obsession with the Kennedys – not the drama or celebrity of them, but their politics. I was driven by that and had a great chance as part of the year abroad to work for Senator Ted Kennedy. I wrote my undergrad dissertation on Bobby Kennedy, a master's thesis on him, and then even a pretty boring academic book.

Playing football while on his year abroad.

And did your degree help you in your career?

Absolutely, yes. I've worked a couple of times for American human rights NGOs, and my degree really helped me understand the US work culture. It probably even helped in getting the jobs. When I applied for those jobs, I'd written one or two books on American history and politics. I don't know if it was a decisive factor, but I think it probably helped.

The work experience I’d had in the USA was a real help as well. It was very different back then – now there’s a whole industry for interns and in development you might be expected to do 2 or 3 of them before applying for full-time positions.

I just wandered into the office in Congress, found Kennedy's office, and said, "Can I volunteer?" They said, "Well, you know, we have this intern thing." I was like, "Alright." That was it.

I opened letters and photocopied press clips, which would be very different nowadays. I started doing bits and pieces of research. Due to my weird experience in South Africa, I got to brief Ted Kennedy about apartheid and do some research on a significant piece of legislation he sponsored - the Anti-Apartheid Sanctions Act. I played a micro part in that. It was great.

And how did you start your career after leaving UEA?

I knew I could write, and so I tried to find a job with that. After coming back to Norwich and finishing my degree in 1986, there weren’t many jobs. A lot of people took call centre jobs, but I went back to working on the buildings, and worked on building sites in London during the day and wrote articles in the evenings on a typewriter. I sent them off to small publications, as I thought it was the best way to get published. This was a different time, without the internet, so I had to type everything out, put it in an envelope, and send it. There was no copy and paste, it was hard going. Eventually, I wrote a few articles for small political publications.

Eventually, I got my first office job at the Catholic Herald, a liberal religious newspaper. It was a great introduction to weekly newspaper work, and I had the opportunity to cover issues I was into, like South African apartheid, and IRA miscarriages of justice cases in Britain. Later, I moved to an African politics magazine in London. In 1991, I joined Amnesty International as a press officer, marking the beginning of my journey in the human rights field. Since then, I've been actively involved in human rights advocacy through my work at Amnesty International and beyond.

And with your Kennedy passion, why did you not continue to write about American politics?

Well, because there wasn't a living in it. I did use to write occasional pieces. I also got into writing book reviews. I mean, it wasn’t lucrative, but it was extra pocket money. Now and then I’d get an article in an American paper, but only a couple of times a year.

Then, I started doing a master's at the Open University, which was a great course. It didn't offer lessons. You just go away for two years and come back with a big fat dissertation, which I wrote on Bobby Kennedy. It was great for somebody in full-time work. There was really no teaching at all.

Are the books you’ve released where you’ve been able to explore topics of most interest to you?

Yes, although I’ve only written three: one about Bobby Kennedy because I was a little bit obsessive. Then, one about the connection between the American Civil Rights Movement and the Irish Civil Rights Movement in the '60s and '70s. I just did it because I wanted to do it, and it was a lot of work before the Internet. Then the third book was really just about the conflict in the north of Ireland although there is also a fair amount about the American influence on that too. The civil rights book I took and used as a basis for the PhD that I went back to UEA with.

So why did you go back to UEA to do a PhD?

I started getting these emails from students, mostly in America, who’d been forced to read one of my books as part of their course, saying, "I've just read your book and, on page 16 you say this, but then on page 87 you say something else.” It was a bit annoying, but it kept me engaged with what I’d written before.

And then I heard that some universities in Britain offer this PhD by publication path. There was a 10% discount for UEA alumni so that helped. I had to enrol again as a student for six months, and I had to basically write an essay on how my book over the last 25 years had been academically influential or important. The internet made that job much more straightforward than I’d imagined. I still had the same UEA registration number from 1982, which was bit scary.

I didn’t get to go to Norwich all that much and I usually used to meet my supervisor, Nick Grant, in London, but I have been back a couple of times to give talks and that’s been great.

You’ve done lots of work on behalf of people in war-torn places. How did that come about?

I’ve always been comfortable going to places that others won’t. I've just tended to gravitate to places that are in war or revolution. I spent some time on research trips to Gaza with Amnesty. The first Pride marches in the Baltics were violent and dangerous. I’ve been to Hong Kong during the revolution, Egypt during the revolution, Bahrain under martial law, and close to the fighting in Ukraine over the last couple of years.

Brian in Ukraine.

What drives your work?

Oh, God. You know, it's a totally fair question, I’ve no idea. I had a very early, dramatic, intense experience when I was 18 or 19, living illegally in a “Blacks Only” area in South Africa. It was an absurd, ridiculous, formative experience, and I should never have been allowed to go, but it totally changed my life for the better. I think it would have been hard for me just to go and do an office job after that. So, I take the work very seriously. I’m 60. I don't particularly feel old, but I realise I'm not going be doing this in 20 years, possibly even 10. So, there's an urgency to it. I work very hard. I don't take much time off.

The privilege of the job for me is never being bored, in going to places to meet people doing extraordinary things, who are taking risks to help others. It’s exciting.

What are you most proud of in your work?

In human rights work, there's an unwritten agreement not to claim credit for successes because the collaborative nature of the work involves lots of people. When positive outcomes happen, it's always a shared effort, and it’s not right or fair that one person takes credit for anything.

But, I would say that I'm proud of still doing it and maintaining the appetite for it. Sometimes, as people gain experience, their enthusiasm may dip. I have as much energy for the work as I ever did.