Study reveals significant increasing nitrous-oxide emissions from human activities, jeopardizing climate goals

By: Communications

Emissions of nitrous-oxide (N2O) - a potent greenhouse gas - have continued to rise unabated over the past four decades, according to an international team of scientists.

The new report 'Global nitrous oxide budget (1980–2020)' is published today in the journal Earth System Science Data. It is the most comprehensive accounting to date of nitrous-oxide emissions from human activities and natural sources.

It was led by researchers from Boston College in the US and involved an international team of scientists including researchers from the University of East Anglia (UEA), UK, under the umbrella of the Global Carbon Project. In total, the team was comprised of 58 researchers from 55 organizations in 15 different countries.

The report reveals that nitrous-oxide emissions from human activities have increased by 40 per cent (3 million metric tons of N2O per year) in the past four decades, resulting in accelerating atmospheric accumulation of this potent greenhouse gas.

Observed atmospheric growth rates over the past three years (2020-2022) have been higher than any previous observed year since 1980, when reliable measurements began.

Like carbon-dioxide (CO2), nitrous-oxide is a long-lived greenhouse gas and contributor to climate change. It also plays an important role in the destruction of the stratospheric ozone layer, which protects the Earth from the Sun’s harmful ultraviolet radiation.

The report reveals that the largest source of nitrous-oxide emissions from human activities comes from agricultural production – this is attributed mainly to the use of commercial nitrogen fertilizers and the use of animal waste on croplands. In addition, the increased levels of nitrogen runoff from fields pollutes inland waters and rivers, and increases N2O emissions from lakes, ponds, and coastal ecosystems.

Agricultural emissions of nitrous-oxide reached 8 million metric tons in 2020 and contributed 74 per cent of the total N2O emissions from human activities in the last decade. Improved practices in agriculture involving the efficient use of nitrogen fertilizers and animal manure will help to reduce nitrous-oxide emissions and water pollution.

The report’s lead author, Hanqin Tian, the Schiller Institute Professor of Global Sustainability at Boston College, said: “Nitrous oxide emissions from human activities must decline in order to limit global temperature rise to 2°C as established by the Paris Agreement. Reducing N2O emissions is the only solution since at this point no technologies exist that can remove N2O from the atmosphere.”

The study draws on millions of N2O measurements taken during the past four decades, as well as on a combination of detailed models of the global nitrogen cycle in land-based systems, oceans and freshwater systems, and the atmosphere.

Prof Parv Suntharalingam, of UEA’s School of Environmental Sciences, is the lead UK author and led on the ocean model component of the report. She said: “The significant growth in N2O emissions in recent years has resulted in observed atmospheric concentrations exceeding the most pessimistic scenarios used in recent IPCC assessments.

“N2O emissions from natural sources, such as the oceans and soils, have remained relatively stable over recent decades. This report highlights that human activities are the most important factor in the observed atmospheric increase, emphasizing the need for effective emissions reduction strategies.”

The concentration of atmospheric N2O reached 336 parts per billion in 2022, a 25 per cent increase over pre-industrial levels that far outpaces predictions previously developed by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, said Prof Tian.

He added: “This emission increase is taking place when the global greenhouse gases should be rapidly declining towards net zero emissions if we have any chances to avoid the worst effects of climate change.”

Some countries have seen success implementing policies and practices to reduce N2O emissions, according to the report. Emissions in China have slowed since the mid-2010s, as have emissions in Europe during the past few decades. In the US, agricultural emissions continue to creep up while industrial emissions have declined slightly, leaving overall emissions rather flat.

Established in 2001, The Global Carbon Project analyzes the impact of human activity on greenhouse gas emissions and Earth systems, producing global budgets for the three dominant greenhouse gases (carbon dioxide, methane, and N2O). These assessments of greenhouse gas emissions and sinks inform further research, policy, and international action.

“While there have been some successful nitrogen reduction initiatives in different regions, we found an acceleration in the rate of N2O accumulation in the atmosphere in this decade,” said Global Carbon Project Executive Director Josep Canadell, who is also a research scientist at CSIRO, Australia’s national science agency.

“The growth rates of atmospheric N2O in 2020 and 2021 were higher than any previous observed year and more than 30 per cent higher than the average rate of increase in the previous decade.”

The researchers say there is a need for more frequent assessments so mitigation efforts can be targeted to high-emission regions and economic activities. An improved inventory of sources and sinks will also be required if progress is going to be made toward the objectives of the Paris Agreement.

‘Global Nitrous Oxide Budget 1980–2020’, Tian et al, is published in Earth System Science Data on June 12, 2024.

Related Articles

Scientists discover how fast the world’s deltas are sinking

New research involving the University of East Anglia (UEA) reveals how fast the world’s deltas are sinking and the human-driven causes.

Read more

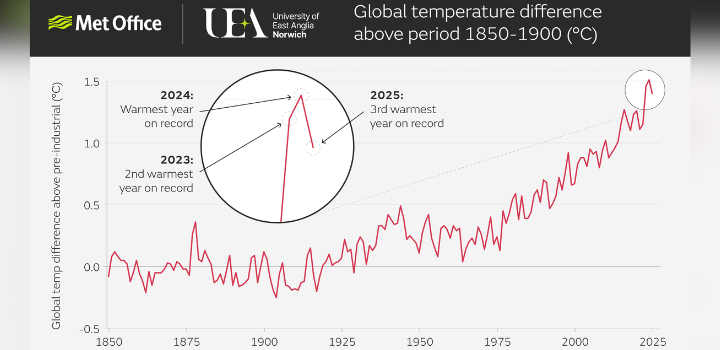

2025 continues series of world’s three warmest years

2025 is the third warmest year on record in a series from 1850, following 2024 and 2023, according to new data released today.

Read more

Overlooked hydrogen emissions are heating Earth and supercharging methane

Rising global emissions of hydrogen over the past three decades have amplified the impact of the greenhouse gas methane and intensified climate change - according to an international team including researchers at the University of East Anglia (UEA).

Read more