Climate change raised the odds of unprecedented wildfires in 2023-24

By: Communications

Unprecedented wildfires in Canada and parts of Amazonia last year were at least three times more likely due to climate change and contributed to high levels of CO2 emissions from burning globally, according to the first edition of a new systematic review.

The State of Wildfires report takes stock of extreme wildfires of the 2023-2024 fire season (March 2023-February 2024), explains their causes, and assesses whether events could have been predicted. It also evaluates how the risk of similar events will change in future under different climate change scenarios.

The report, which will be published annually, is co-led by the University of East Anglia (UEA, UK), the UK Centre for Ecology & Hydrology (UKCEH), the Met Office (UK) and European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts (ECMWF, UK).

Published today in the journal Earth System Science Data, the report finds that carbon emissions from wildfires globally were 16% above average, totalling 8.6 billion tonnes of carbon dioxide. Emissions from fires in the Canadian boreal forests were over nine times the average of the past two decades and contributed almost a quarter of the global emissions.

If it had not been a quiet fire season in the African savannahs, then the 2023-24 fire season would have set a new record for CO2 emissions from fires globally.

As well as generating large CO2 emissions, fires in Canada led to more than 230,000 evacuations and eight firefighters lost their lives. An unusually high number of fires were also seen in northern parts of South America, particularly in Brazil’s Amazonas state and in neighbouring areas of Bolivia, Peru, and Venezuela. This led to the Amazon region experiencing among the worst air quality ratings on the planet.

Elsewhere in the world, individual wildfires that burned intensely and spread quickly in Chile, Hawaii, and Greece led to 131, 100, and 19 direct fatalities, respectively. These were among the many wildfires worldwide with significant impacts on society, the economy, and the environment.

“Last year, we saw wildfires killing people, destroying properties and infrastructure, causing mass evacuations, threatening livelihoods, and damaging vital ecosystems,” said the lead author of this year’s analysis, Dr Matthew Jones, Research Fellow at the Tyndall Centre for Climate Change Research at UEA.

“Wildfires are becoming more frequent and intense as the climate warms, and both society and the environment are suffering from the consequences.”

The loss of carbon stocks from boreal forests in Canada and tropical forests in South America have lasting implications for the Earth’s climate. Forests take decades to centuries to recover from fire disturbance, meaning that extreme fire years such as 2023-24 result in a lasting deficit in carbon storage for many years to come.

“In Canada, almost a decade’s worth of carbon emissions from fire were recorded in a single fire season - more than 2 billion tonnes of CO2,” said Dr Jones. “In turn, this raises atmospheric concentrations of CO2 and exacerbates global warming.”

Climate change made the 2023-24 fire season more extreme

As well as cataloguing high-impact fires globally, the report focused on explaining the causes of extreme fire extent in three regions: Canada, western Amazonia, and Greece.

Fire weather - characterised by hot, dry conditions that promote fire - has shifted significantly in all three focal regions when compared to a world without climate change. Climate change made the extreme fire-prone weather of 2023-24 at least three times more likely in Canada, 20 times more likely in Amazonia, and twice as likely in Greece.

The report also used cutting-edge attribution tools to distinguish how climate change has altered the area burned by fires versus a world without climate change. It found that the vast extent of wildfires in Canada and Amazonia in the 2023-24 fire season was almost certainly greater due to climate change (with more than 99% confidence).

“It is virtually certain that fires were larger during the 2023 wildfires in Canada and Amazonia due to climate change,” said Dr Chantelle Burton, Senior Climate Scientist at the Met Office.

“We are already seeing the impact of climate change on weather patterns all over the world, and this is disrupting normal fire regimes in many regions. It is important for fire research to explore how climate change is affecting fires, which gives insights into how they may change further in the future.”

Likelihood of extreme wildfires will rise but can be mitigated

Climate models used in the report suggest that the frequency and intensity of extreme wildfires will increase by the end of the century, particularly in future scenarios where greenhouse gas emissions remain high.

The report shows that by 2100, under a mid-to-high greenhouse gas emissions scenario (SSP370), wildfires similar in scale to the 2023-24 season will become over six times more common in Canada. Western Amazonia could see an extreme fire season like 2023-24 almost three times more frequently. Similarly, years with fires on the scale of those seen in Greece during 2023-2024 are projected to double in frequency.

“As long as greenhouse gas emissions continue to rise, the risk of extreme wildfires will escalate,” said Dr Douglas Kelley, Senior Fire Scientist at UKCEH.

Increases in the future likelihood of extreme wildfire events, on the scale of 2023-2024, can be minimised by reducing greenhouse gas emissions. Following a low emissions scenario (SSP126) can limit the future likelihood of extreme fires. In western Amazonia, the frequency of events like 2023-24 is projected to be no larger in 2100 than in the current decade under a low emissions scenario. In Canada, the future increase in frequency of extreme fires is reduced from a factor of six to a factor of two, while in Greece the increase is limited to 30%.

“Whatever emissions scenario we follow, risks of extreme wildfires will increase in Canada, highlighting that society must not only cut emissions but also adapt to changing wildfire risks,” said Dr Kelley.

“These projections highlight the urgent need to rapidly reduce greenhouse gas emissions and manage vegetation in order to reduce the risk and impacts of increasingly severe wildfires on society and ecosystems.”

Disentangling the causes of extreme fires

Several factors control fire, including weather conditions influenced by climate change, the density of vegetation on the landscape influenced by climate and land management, and ignition opportunities influenced by people and lightning.

Disentangling the influence of these factors can be complex, but the report used cutting-edge fire models to reveal the influence of different factors on extreme fire activity.

The report found that the area burned by fires in Canada and Greece would likely have been larger if the landscape had not been altered by people. Activities such as agriculture, forestry, and dedicated fire management efforts all influence the landscape, and can reduce the density of vegetation. In addition, firefighters also help to reduce fire spread by tackling active wildfires. When wildfires meet areas with sparse vegetation or more aggressive firefighting strategies, they can run out of fuel or be contained.

“In Canada and Greece, a mix of severe fire weather and plenty of dry vegetation reinforced one another to drive a major uptick in the number and extent of fires last year,” said Dr Francesca Di Giuseppe, Senior Scientist at ECMWF.

She added: “But our analysis also shows that factors such as suppression and landscape fragmentation related to human activities likely played important roles in limiting the final extent of the burned areas.

“Human practices played an important role in the most extreme events we analysed. However, we found that the final extent of these fires was determined by the simultaneous occurrence of multiple predictable factors — principally weather, fuel abundance, and moisture — rather than direct human influence.”

The report found that human activities increased the extent of the 2023 wildfires in western Amazonia. In this region, the expansion of agriculture has resulted in widespread deforestation and forest degradation. This has left forests more vulnerable to fire during periods of drought and fire weather, amplifying the effect of climate change.

During 2023-24, the fourth most powerful El Niño event on record drove a prolonged drought and heatwave in South America. This natural feature of Earth’s climate increases temperatures and reduces rainfall in Amazonia every three to eight years, but it is increasingly superimposed on higher temperatures due to climate change.

“In many tropical forests like Amazonia, deforestation and the expansion of agriculture have exacerbated the effects of climate change on wildfire risk, leaving these vital ecosystems more vulnerable,” said Dr Burton.

An eye towards the 2024-2025 fire season

Forecasting fire risk is a growing research area and early warning systems have already been built based on weather factors alone. For example, in Canada, extreme fire weather was predicted two months in advance and provided early indications of high fire potential in 2023. Events in Greece and Amazonia had shorter windows of predictability.

For the 2024-25 season, forecasts suggested a continued above-average likelihood of fire weather - hot, dry, and windy conditions - in parts of North and South America, which presented favourable conditions for wildfires in California, Alberta, British Columbia, and in the Brazilian Pantanal in June and July.

Dr Di Giuseppe said: “We're not particularly surprised by some of the recent fires in the news, as above-average fire weather was predicted in parts of North and South America. However, the extensive Arctic fires we've witnessed recently have caught us by surprise — something to look at in our next report.”

To accompany the report, an interactive atlas and timeseries chart have been created, showing extremes of the 2023-2024 fire season by country and by burned area, CO2 emissions, and number of fires.

If you are looking to start university in September 2024 and still thinking about your options, consider joining a UK Top 25 university this September through Clearing.

Related Articles

Review of wildfire activity in 2023 reveals where record area burned

An overview of global wildfire activity and impacts for last year reveals the parts of the world that saw a record amount of area burned.

Read more

Scientists discover how fast the world’s deltas are sinking

New research involving the University of East Anglia (UEA) reveals how fast the world’s deltas are sinking and the human-driven causes.

Read more

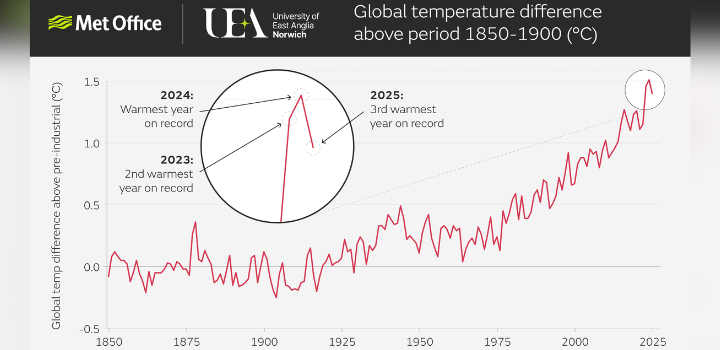

2025 continues series of world’s three warmest years

2025 is the third warmest year on record in a series from 1850, following 2024 and 2023, according to new data released today.

Read more