2023: the warmest year on record globally

By: Communications

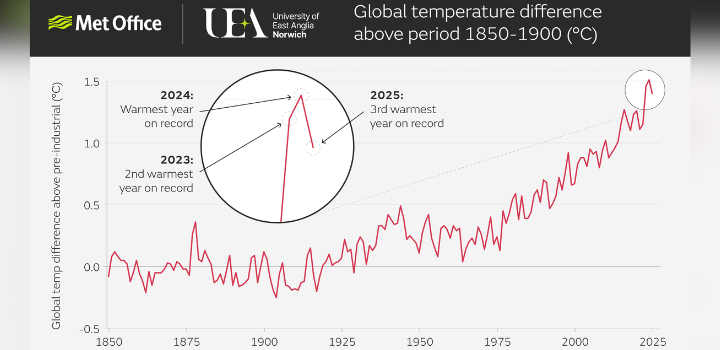

Globally 2023 was the warmest year in a series stretching back to 1850, according to figures released today by the University of East Anglia and the Met Office.

2023 is the tenth year in succession that has equalled or exceeded 1.0 °C above the pre-industrial period (1850-1900).

The global average temperature for 2023 was 1.46 °C above the pre-industrial baseline; 0.17 °C warmer than the value for 2016, the previous warmest year on record in the HadCRUT5 global temperature dataset which runs from 1850.

Professor Tim Osborn, of the University of East Anglia’s Climatic Research Unit, said: “Twenty-five years ago, 1998 was a record-breaking year for global average temperature. But last year’s global temperature was 0.5 °C warmer than 1998, providing further evidence that our planet is warming on average by 0.2 °C per decade.

“At the current rate of human-induced warming, 2023’s record-breaking values will in time be considered to be cool in comparison with what projections of our future climate suggest.”

Dr Colin Morice is a Climate Monitoring and Research Scientist with the Met Office. He said: “2023 is now confirmed as the warmest year on average over the globe in 174-years of observation. 2023 also set a series of monthly records, monthly global average temperatures having remained at record levels since June. Ocean surface temperatures have remained at record levels since April.

“Year-to-year variations sit on a background of around 1.25 °C warming in global average temperatures above pre-industrial levels. This warming is attributable to human-induced climate change through greenhouse gas emissions.”

On top of the long-term warming, a transition into El Niño conditions contributed to further elevated temperatures for the latter part of the year. El Niño is part of a pattern of climate variability in the tropical Pacific that imparts warmth to the global atmosphere, temporarily adding up to 0.2 °C to the temperature of an individual year. This stands in contrast to the reverse pattern of climate variability, La Niña, which suppressed global average temperatures in 2021 and 2022.

Prof Philip Jones, Professorial Fellow at UEA’s Climatic Research Unit, said: “I've been working with the global temperature series since the early 1980s. There has never been a year like 2023 where the warmest-ever June, warmest-ever July through to the warmest-ever December was recorded for seven months in a row, from June to December, 2023.”

Outlook for 2024

Professor Adam Scaife is a Principal Fellow and Head of Monthly to Decadal Prediction at the Met Office. He said: “It is striking that the temperature record for 2023 has broken the previous record set in 2016 by so much because the main effect of the current El Niño will come in 2024. Consistent with this, the Met Office’s 2024 temperature forecast shows this year has strong potential to be another record-breaking year.”

The Met Office global temperature for 2024 is forecast to be between 1.34 °C and 1.58 °C (with a central estimate of 1.46 °C) above the average for the pre-industrial period (1850-1900): the 11th year in succession that temperatures will have reached at least 1.0 °C above pre-industrial levels.

HadCRUT5

The HadCRUT5 dataset is compiled by the Met Office and the University of East Anglia (UEA), with support from the National Centre for Atmospheric Science. It shows that when compared with the pre-industrial reference period, 2023 was 1.46 ± 0.1 °C above the 1850-1900 average. This aligns extremely well with figures published today by other international centres.

Other data sets

The World Meteorological Organization uses six international data sets to provide an authoritative assessment of global temperature change. They report 2023 was around 1.45 ± 0.12°C warmer than the 1850-1900 baseline based on an average of the six data sets.

The long-term warming is clear. Since the 1980s, each decade has been warmer than the previous one.

Importance of global mean temperature

Global average temperature is the key measure of climate change, providing a headline metric that is expanded upon by the changing patterns of rainfall, drought, ice, temperature and extreme weather that are associated with a warming climate. You can see the impact on other key climate indicators on the Met Office global climate dashboard.

It is complex and challenging to track the average temperature of an entire planet, using around a billion temperature observations from the last 174 years.

The UK’s contribution to measuring this key indicator of climate change is led by scientists at the Met Office, UEA and NCAS. This ongoing work is crucial as the world moves still closer to the limits set out in the Paris Agreement.

Defining global temperature change relevant to the Paris Agreement

While the global average temperature in a particular year is well-known, this will not be suitable as an indicator of whether the “Paris 1.5” has been breached or not, because the Paris Agreement refers to long-term warming, not individual years. But no alternative has yet been formally agreed.

In a recent paper published in Nature, Met Office scientist Prof Richard Betts and coauthors proposed an indicator combining the last ten years of global temperature observations with an estimate of the projection or forecast for the next ten years. If adopted by the international community this could mean a universally agreed measure of global warming that could trigger immediate action to avoid further rises.

Using this suggested approach, the researchers found that the figure for the current global warming level, relevant to the Paris Agreement, is around 1.26 °C, with an uncertainty range of 1.13 °C to 1.43 °C.

Want to understand the science behind the calculation of the 1.5°C figure that underlies climate change negotiations across the planet? Read UEA's explainer from our experts: https://www.uea.ac.uk/climate/resources-and-blogs/unpacking-the-1.5%C2%B0c-temperature-increase

Related Articles

Scientists discover how fast the world’s deltas are sinking

New research involving the University of East Anglia (UEA) reveals how fast the world’s deltas are sinking and the human-driven causes.

Read more

2025 continues series of world’s three warmest years

2025 is the third warmest year on record in a series from 1850, following 2024 and 2023, according to new data released today.

Read more

Overlooked hydrogen emissions are heating Earth and supercharging methane

Rising global emissions of hydrogen over the past three decades have amplified the impact of the greenhouse gas methane and intensified climate change - according to an international team including researchers at the University of East Anglia (UEA).

Read more